MORE TO EXPLORE

GENERAL MANUFACTURE PROCESS

All tea categories are made from freshly picked leaves of the Camellia Sinensis. We found six categories of teas determined by the manufacturing method and different levels of oxidation and fermentation that takes place during processing.

WHITE TEA: Goes through extremely light, slow, spontaneous oxidation.

GREEN TEA: Is not oxidized.

YELLOW TEA: Is not oxidized, but is lightly fermented.

OOLONG TEA: Is partially oxidized.

BLACK TEA: Is fully oxidized.

DARK TEA: Goes through a process of post-manufacture oxidation and microbial fermentation.

Once the leaves are plucked from the plant, they must be taken as quickly as possible to the factory for processing, as they tend to quickly oxidize once they are removed from the tea plant (just as apples in contact with oxygen).

To create a high-quality tea, the process includes several stages.

TERMS USED

Plucking

Process used to extract leaves from the tea plant. The way a person plucks the leaves plays an important role in the taste and aromas of the resulting tea; the rule is you can’t make good tea from a badly plucked tea leaf. Plucking triggers a tea bush to produce a sweet sap, which are the chemicals responsible for the unique taste and aroma of tea. Also, if a bush or tree is plucked too aggressively, the plant can be severely damaged or be killed.

The plucked leaves are collected in a basket or bag carried on the back of the plucker. In the collection point they are weighed and checked to verify if the collected leaves comply with the standards of quality before going to the factory for processing.

On slope terrain, tea is still hand-plucked, a laborious task performed mostly by women (a skilled plucker can gather between 30-35 kg of leaves a day, enough to produce around 6-7 kl of processed black tea).

Most gardens “table” their plants, pruning them to grow no higher than shoulder height, which makes it easier to pluck the leaves. (This is style of growing also creates stunning landscapes of perfectly trimmed rows of undulating tea bushes growing on the sides of the mountains!).

Withering

After plucking, the tea is transported to the production facility. The leaves are then withered to reduce the moister content, making them soft and pliable, easier to manipulate in subsequent processes. Leaves are spread out, either in the sun, or in trays in a controlled well-ventilated inside environment, or both.

According to the type of tea, time vary, but all teas go through at least a short withering; without it, it would be very difficult for a tea master to create the beautiful and distinctive shapes of tea.

Rolling

Once withered, the leaves are ready for the rolling stage, where they are pressed either by hand or by rolling machines (big circular rotators that press the leaves between two grooved wooden plates which tear, squeeze, and bruise the leaves).

The main purpose of this stage is to squeeze out more moisture and break down the cells in the leaves to encourage a faster and fuller oxidation for oolong and black teas. It causes as well aromatic and flavor compounds, or tea juices, to develop (once dried, the leaves “lock” them, releasing them in the cup when brewed!).

Oxidation

When the cells of freshly plucked tea leaves are broken, bruised, or cut, various components react on them in contact with the oxygen, and a chemical reaction begins.

Green teas stop oxidation by applying heat to the leaves. But for black and most oolongs, further oxidation is required.

After rolling, the tea leaves are laid out to oxidize in tables in a humid environment. This period can be from 30 minutes to 5 hours, lasting until the tea master decides that oxidation has concluded (for black tea), or desired level has been reached (for oolong).

After oxidation, the leaves look very different from how they started, being darker in color (the green chlorophyll in the leaves changes to brown pigments) and aroma and flavor also undergo change as the tea gains briskness and strength.

Drying

In order to halt the oxidation process and further reduce the moister content, the leaves are then dried using dryers or ovens. Once dried, the flavors will stay as they are until the tea is brewed.

Fermentation

Most important to the production of dark and yellow tea is the process of fermentation, as a result of microbial and/or bacterial activity and is often provoked by humidity and warmth.

Fermentation happens in yellow teas when steam is purposely trapped in the tea during manufacture.

It takes place in dark teas as a result of humidity, warmth, and the activity of molds in the tea. After rolling, puerh teas are steamed and compressed into cakes, bricks, or various shapes (while others are sold loose) and left to age and ferment. In the past, puerh teas would ferment on the long journey from China via the Tea Horse Road, these days undergo different ripening processes.

Fixing the green

In green teas -in order to stop any oxidation- dry heat (in China) or steam (in Japan) is applied to the leaf, to fix the green color and flavor. This process is also called “fixing or killing the green”.

Dry heat is applied in a hot, dry wok or a panning machine.

To apply steam, the leaves are placed inside a cylinder or drum in which steam is injected, and they are tumble for some seconds to ensure that they are all evenly heat-treated.

Dry heat tends to take longer than steaming, so panned teas often have more complex flavors than do steamed varieties.

Sorting and Packing

Once processed, leaves are either hand-sorted or machine-sorted, allowing the leaves to separate according to size (and are graded), and separate out unwanted elements, such as stems.

A well-produced orthodox tea will have fewer small pieces of leaf and more whole leaves, which are considered a higher grade.

In the packing room, the leaves are packed into aluminum-lined paper sacks and stamped with the tea’s grade, weight, package date and factory/estate origin.

LEGENDS AROUND SOME TEAS

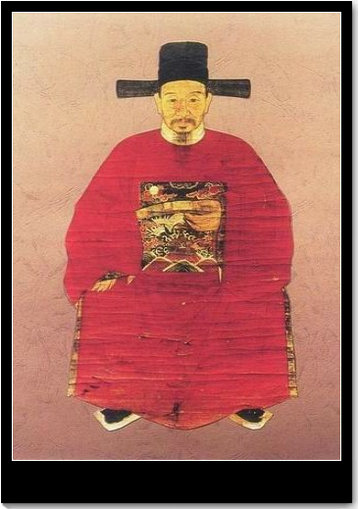

Legend of Da Hong Pao (Big Red Robe)

By JANE PETTIGREW, tea specialist, from the UK Tea Academy

“One legend states that the mother of a Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) emperor was cured of an illness by tea made from these bushes. The Emperor then sent his “da hong pao” (big red rob) to clothe the four bushes in order to honor them and recognize their great power.

Another legend says that a mandarin once fell ill while travelling in the Wuyi mountains and nothing would cure him, until a local monk made tea from leaves and buds plucked from these 4 bushes. The infusion from the leaves cured him and when he returned to Beijing, he told the emperor about the miraculous tea bushes. The emperor sent his red robe to protect and honor the bushes”.

Tea of The Iron Goddness of Mercy (Ti Kuan Yin)

By JANE PETTIGREW, tea specialist, from the UK Tea Academy

“Legend says that a farmer in Anxi country, Fujian province, had a small tea garden. On his way to work each day he passed a small, neglected shrine to Kuan Yin, the Goddess of Mercy. He decided to tidy it, weed the garden around it, put fresh flowers on the altar and look after it.

One night, several months later, the tea farmer had a dream in which the iron statue of the goddess told him to look behind the shrine on his way to work the next day, and he would find a treasure. All he found was a new tea shoot, which he took and planted in his tea garden. When the bush was mature enough to start harvesting, he plucked the new leaves and buds and the tea he made was so delicious that it made him a fortune. Ti Kuan Yin tea became very famous”.

Legend on Shui Xian Wuyi Oolong

By MISHA from “PATH OF CHA”

“One village on the foot of Wuyishan had a particularly curious monk living in the local temple. He wished to see where all the rivers originate. So, he set out on a long journey up the rocky slopes of the Wuyi Mountains.

Once at the top, fully surrounded by fog, clouds, and mist, he saw a figure. It was the Wise Tea Master Lao Cha. He took him to a tea bush and brewed the leaves.

The monk was at a loss for words. He felt that the tea had the spirit of all the mountains, rivers, and oceans of the entire world.

-What is the tea, oh wise one?

– Shui Xian Wuyi Oolong. Now go on, take this tea back to your village where fellows can enjoy it for centuries to come.”

Legend on "Golden Turtle" Shui Jin Gui Wuyi Oolong

By MISHA from “PATH OF CHA”

“The legend of the Golden Water Turtle dates way back when Wuyi mountain dwellers lived high on the slopes, cultivating delicious tea bushes. One day a strong storm washed down the tea bushes, along with clay and rocks, onto another farmland. Once the storm passed, the tea bush growing from the mud resembled a swimming longevity turtle, hence the Water Turtle name.

Today, only three original tea bushes remain. While these bushes are subject to strict protective measures, and no one can harvest their tea leaves, our Shui Jin Gui is descending from them.”

“A disciple asked the wise, and very old, tea master Lao Cha, of his secret to longevity.

Golden Water Turtle — he answered, offering a small cup of tea.

Puzzled, the disciple took a sip. The unique Yan Yun, the minerals, the notes of heart-warming chocolate, and the sweet roasted taste… all enveloped his body and soul. The disciple had no further questions.”

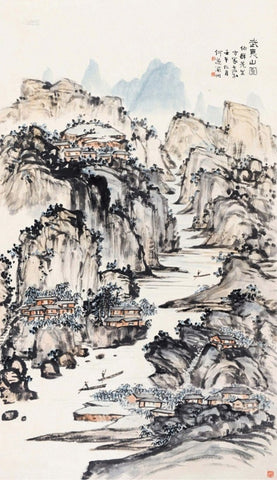

WUYI MOUNTAIN TEA – CLIFF TEA

There is a particular type of oolong tea that grows in the Chinese Wuyi mountains in Fujian Province, called the Wuyi rock tea or Cliff tea.

The most famous Wuyi Mountain teas are Da Hong Pao and Lapsang Souchong (the forefather of all black tea).

The Wuyi mountain region has been an important tea production area since mid-17th century, relatively new within the vast history of tea, but continues to be so.

The prime Wuyi Mountain tea growing area has 39 peaks, 72 caves and 99 cliffs.

The peaks are constantly shrouded with fog and mist. The moister settles on the rocky sides of the mountain slopes, bringing on their way down rich minerals to the root of the plants, adding a particular rocky taste to the teas produced there. These unique terroir conditions are what makes this tea so special.

Wuyi oolongs have a heavy roast with robust flavors. The rocky and minerals profiles are perfectly balanced with the sweet and floral notes.

Their leaves are twisted into thin strips rather than balled shaped.

Rock tea can be extremely expensive, but many, though incredibly delicious and memorable, are while affordable.

ZHENG YAN

Translates as “original rock”. In 1999 the Chinese government designated de Zhengyuan area of the Wuyi Mountains as the Wuyi World Heritage Reserve.

This area has many original tea cultivars. Since the government prohibits pesticides on the ground of the whole reserve, all the teas are organic (tending so to be of a higher price).1

The most popular Wuyi Oolongs are:

“THE FOUR BIG AND FAMOUS BUSHES”

- Da Hong Pao

- Shui Jing Gui

- Tie Luo Han

- Bai Ji Guan

OTHER FAMOUS WUYI OOLONGS

- Rou Gui

- Shui Xian

- Bei Dou

- Huang Guan Yin

DA HONG PAO

The yield that comes from the original mother plants is so small that it is considered a national treasure and doesn’t get on the market at all (distributed among a few, reserved for decades ahead).

It is said that the 99% of Da Hong Pao on the market today is either a blend of two cultivars -ROU GUI and SHUI XIAN-, or a Qi Dan that grows outside the main Wuyi Mountain Nature Preserve.

SHUI JING GUI (GOLDEN WATER TURTLE)

Golden Water Turtle or Shui Jin Gui, is a famous Wuyi Oolong, one of the “four big and famous bushes” among the Northern Fujian teas.

This Cliff tea is roasted three times over a traditional charcoal fire, turning it into an incredible smooth tea, medium roast, with an unexpectedly sweet floral after taste. Peach, exotic flowers, and dark chocolate blend together, gently revealing wood, for a cup comforting and refreshing at the same time.

You can learn more about the Shui Jing Gui Legend Here

RO GUI (CHINESE CINNAMON)

One of Fujian Province’s famous rock oolongs. Also known as Cassia Oolong, Wuyi Cassia Oolong and Cassia Bark.

Its long leaves are dark, green-brown, lightly curled, and have a sweet and spicy aroma of cassia, a cinnamon like cortex.

The liquor is clear golden amber, with a honey and orchid aroma and a full, rich, slightly smoky flavor with a citrus aftertaste.

SHUI XIAN

Also known as “Narcissus” or “Water Sprite” in the West, and “tea of immortality”.

Shui Xian is a signature cultivar for Northern Fujian, one of the main oolong types to this region. It is hand-picked from 40 year of tea trees and is organic as Zheng Yan, the prime area of Wuyi Mountain where this Cliff Tea is grown, is a National Reserve area with a strict prohibition of pesticides usage.

It has an intense flower fragrance with dominating orchid notes. The liquor is clear and bright deep orange, with a strong and mellow taste that is equally refreshing and sweet, with caramel honey hints with lingering floral and mineral notes.

Since Shui Xian Oolong is the most widely consumed type of these teas, the tea bushes occupy the most extensive growing area of the Wuyi Mountains.

You can learn more about the Shui Xian Legend here#shui-xian-wuyi

CAMELIA SINENSIS

Although no one location has been categorically defined as tea´s birthplace, the majority view appears to be that the plant first comes from China´s Yunnan Province (and possibly also in Sichuan and and Guizhou provinces), during Earth´s Tertiary geological period from 66 million to 2.58 million years ago.

Ancient tea trees in Yunnan Province, where some tea trees are thought to be at least 2.000 years old.

The Tea plant is classified scientifically as CAMELLIA SINENSIS.

This evergreen plant grows in the shade (or semi-shade), of woodlands and forests and prefers deep, light sandy or loamy soils with an acidic PH between 4.5 – 5.5. The roots need plenty of water, but the ground must be well drained.

The different types need varying temperatures for successful growth.

Tea blossom from a tea plant at THE ROSE TEA SHOP, originating from Agricola Himalaya´s Bitaco Tea Estate in Colombia

Its white flowers have fragile petals, sometimes tinged with hints of pale pink and surround a whorl of bright yellow stamens.

Three natural subspecies of Camellia Sinensis are recognized. The two that are cultivated are, Camellia sinensis var. sinensis, commonly known as the Chinese variety, and the Camelia sinensis var. assamica, commonly known as the Assam variety.

The third type which is rarely used for commercial cultivation is known as the Cambodia variety.

VAR. ASSAMICA

The Assam subspecies was first found there by Europeans in the early 19th century.

It is taller than the Chinese plant and, if left to grow without human intervention, can reach heights of 18 mts.

The leaves are shiny, long (8-30 cm), and much larger than those of the Chinese plant (it is often referred to as the big-leafed variety) and have distinct veins throughout each leave.

In general, the leaves of the Assamica variety contain higher levels of caffeine and polyphenols than those of the Chinese variety.

Native to Assam, China, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos and Vietnam.

This large-leaf varietal loves low-lying, hot, humidity locations where plentiful rainfall nourishes them and encourages fast growth.

It is particularly well suited to the manufacture of black teas, and the majority of the crop is processed as traditional Assam black tea.

In the winter months, the plant stops flushing and wait for the first warmth and spring rain to form new shots. The early buds and young leaves that are gathered in March and April give black teas slightly grassy, fresh and astringent.

More often used for blends than sold as self-drinkers.

Assam’s best second flush teas are harvested in May and June and are manufactured either as orthodox or CTC teas, depending on the demands of the world market.

The dark brown twisted leaves of the second flush orthodox teas are often mingled with “golden tips”, younger buds that shows careful plucking and manufacture.

The CTC teas are stronger, punchier, and more robust but have the same sweet, smooth, malty character as the orthodox teas.

VAR. SINENSIS

The Chinese variety grows to a height of 3 to 4 metres, and when mature forms a dome shape. Its leaves are small, narrow, thick and mate (1-6 cm long and 1.5-2 cm wide).

The plant prefers the cool temperatures of high mountain slopes. During colder seasons, it is dormant and starts forming new leaf shoots only with the spring warm sunshine and the first early rain showers.

Native to China and Japan.

VAR. CAMBODIENSIS

It is a hybrid of var. sinensis and var. assamica.

It grows as a sturdy and very productive small tree. Its glossy leaves are larger than the Chinese variety but smaller than the Assamica type.

Because of its ability to easily hybridise, it is sometimes used in the creation of new cultivars.

Native to Assam, Myanmar and Vietnam.

SPECIALTY TEAS

Specialty tea -fine-premium tea or high-grade loose-leaf tea- is tea that is produced to have unique and exceptional qualities. Its leaves must be whole to reveal their distinctive flavor and characteristics. They are sometimes blended or scented with other ingredients as citrus or smoke.

Just as with fine wine, fine tea has a specific flavor profile that varies from year to year and is known for its terroir in which is produced. Specialty teas in the same classes will taste differently depending on where they are grown and processed. Very important aspects of specialty tea are the season in which the leaves are harvested and the elevation at which the plants are grown.

Most specialty teas are a blend of teas that have been combined to produce an optimal cup for drinking. There are three basic types of blends:

- Single-estate teas, are blended from several days of plucking on the same state.

- Single-origin teas, are blends put together estates within a specific area, either a region within a country or a single country. (Ex. Assam)

- Blending leaves from various countries (Ex. English Breakfast, mix of black teas from India, Sri Lanka, Kenia and sometimes China)

SCENTED AND FLAVORED TEAS

Teas (of any of the six varieties), can be scented or flavored with flowers (petals, pollen heads), fruits (dried pieces), spices, herbs (dried) or essential oils, thanks to its HYGROSCOPIC properties, that is, the ability to absorb fragrances as well as moisture from the air.

Scented teas are made by exposing a finished tea to a desirable scent, such as that of rose, Osmanthus or jasmine flowers.

Tea can also be scented with smoke, such as the famous Lapsang Souchong, which gets its distinctive smoky character from exposing black teas to the smoke from a pine wood fire.

Flavored teas are made by adding a flavoring oil or other flavoring agents. Example, the famed Earl Grey tea, which is black tea infused with either bergamot peel or bergamot oil. Spice flavored teas are also popular as Masala Chai, which typically blends cardamom, cinnamon, cloves, ginger and other spices with black tea.

COMPRESSED TEAS

During the Tang Dynasty (618’906 AD), tea producers started compressing processed tea leaves into cakes of bricks in order to conserve them and make it easier to transport, as they are less susceptible to physical damage along trade routes.

The teas are usually compressed into various shapes than include logs, cakes as flat circles, rectangular or square slabs or bricks, neat little balls, and bird’s nests.

Some are wrapped in bamboo or dried banana leaves while others are packed in rice or simple paper. They can be packed singly or in a stack of four, seven or more cakes.

To brew compressed teas, the desired amount is broken off with the fingers (or you may need a special knife if it is compressed into a hard shape), and then steeped in hot water for 1-5 minutes. The longer time, the darker the color of the liquor and the stronger the flavor.